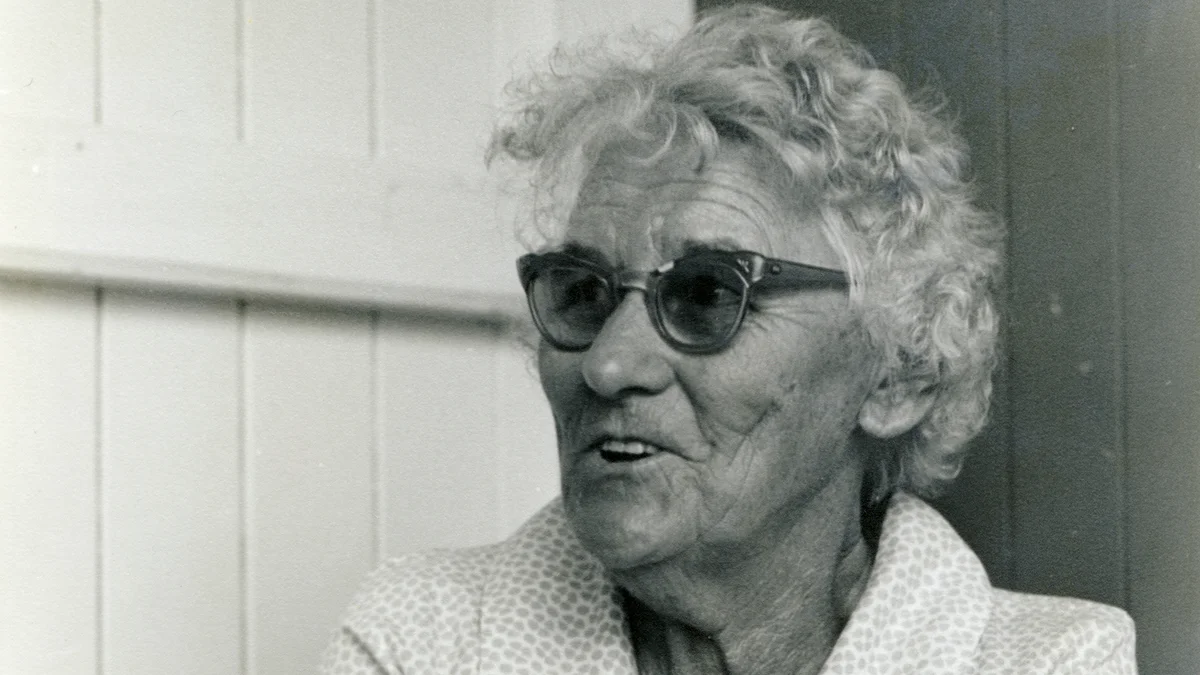

Mary Ferris oral history

Mary recalls growing up at Bankfoot House, Glass House Mountains

Interview with: Mary Isabella Ferris nee: Burgess

Date of Interview: 14 May 1987

Interviewer: Amanda Wilson

Transcriber: Denise Hall

Born: 1902 at Bankfoot House, Glass House Mountains

Married: 19 February 1925 at Red Hill, Brisbane

Children: Five

Mary recalls memories of growing up at Bankfoot House, Glass House Mountains, William Grigor's arrival in Australia and working for William Pettigrew, First Settler in Glass House Mountains District. Mary also talks about Cobb & Co Coaches travelling from Gympie to Brisbane and back - the timetable and accommodation and meal fees at Bankfoot House. Mary remembers the arrival of Halley’s Comet in 1910.

Recollections of Landsborough township and Henry Dyer and John Tytherleigh, the moving of the Mellum Club Hotel Landsborough, the visit of the Prince of Wales in 1920 and the opening of the Landsborough Shire Council Chambers by Uncle, John Grigor in 1924.

Access the Mary Ferris oral history audio files and transcript on Sunshine Coast Life.

Images and documents of the Ferris Family in the Sunshine Coast Libraries Catalogue.