Early history

From the time of the Bunya feasts

Sunshine Coast Council acknowledges the Kabi Kabi and Jinibara Peoples as the traditional custodians of the Sunshine Coast, and wishes to pay respect to their elders past, present and emerging. Council acknowledges the important role Aboriginal and Torres Strait people play within the wider Sunshine Coast community, but also understands and acknowledges that the traditional custodians of the Sunshine Coast have cultural, spiritual, social and economic connections and responsibilities to their traditional lands that are separate to those associated with the wider community. Where possible, Sunshine Coast Council works with the traditional custodians of the Sunshine Coast to demonstrate their understanding of the connections, responsibilities and rights held by the Kabi Kabi and Jinibara Peoples.

The Jinibara People

Jinibara People Aboriginal Corporation (JPAC)

For matters relating to the Sunshine Coast contact:

Jason Murphy, Cultural Heritage Coordinator

JPAC

Business & Economic Development team

87 Woodrow Road, Stanmore 4514, QLD

Contact above for bookings for "Welcome to Country" introductions, cultural heritage advice, cultural talks and workshops, and the Jinibara Song and Dance Troupe. Fees may be involved. Jinibara wooden artefacts are available for sale.

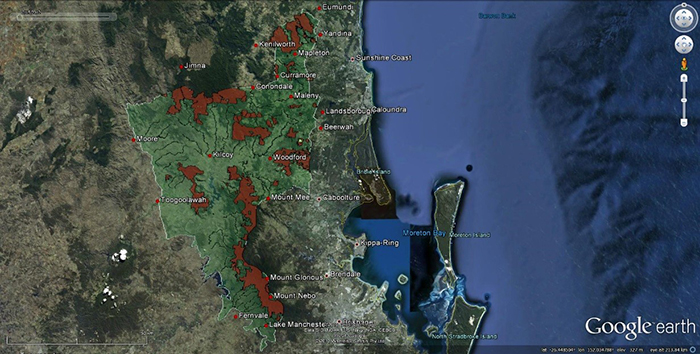

The Jinibara People [1] are the determined native title holders for an area that incorporates the western section of the Sunshine Coast Regional Council and Moreton Regional Council, as well as parts of Brisbane City Council and Somerset Regional Council (see Map 1).

Map 1: Map showing the determined native title area of the Jinibara People

As native title holders, the Jinibara People have been determined through a process in accordance with requirements of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). In addition, and in accordance with the State’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2003, the Jinibara People are also the Aboriginal Party for the country within the external boundaries of the determined native title area shown in Map 1.

Following traditional law, the Jinibara People can only speak for Jinibara traditional country. Within the boundary of Sunshine Coast Council, effectively Jinibara traditional country is west of Old Gympie Road, and the Blackall Ranges. The Jinibara People acknowledge the Kabi Kabi First National People as their neighbours and the traditional custodians of the coastal plains and the Mary River Valley. To the Jinibara People, the Kabi Kabi People are known as mwoirnewar, the saltwater people. The wider community should understand that while the Jinibara and Kabi Kabi Peoples each acknowledge the other as neighbours, there is no so-called shared country. The boundary between these two separate groups has been authorised by both groups. In summary, the Jinibara People only speak for Jinibara traditional country, and reasonably expect their neighbours to follow traditional law by only speaking for Kabi Kabi traditional country.

The Jinibara People are the mountain people. The tribal name of Jinibara means this by implication, as bara means "people" and Jini means "lawyer vine". In other words, the Jinibara People are the "people of the lawyer vine", the traditional people who live in the mountains and valleys where lawyer vine grows. The Jinibara People consists of four sub-groups or clans, being the Dungidau centred on Kilcoy, Villeneuve and Mt Archer area, the Dala from around Woodford and Mt Mee, the Nalbo of the Blackall Range and much of the Glasshouse Mountains, and the Garumngar from the rolling country between the Brisbane River and what today is the southern edge of Brisbane Forest Park around Lake Manchester and Mt. Crosby. Today, the Jinibara families represent all four sub-groups, and work together cohesively through their prescribed body corporate, the Jinibara People Aboriginal Corporation (JPAC).

When describing Jinibara traditional society, it is important to understand its complexity. Individuals inherited their connection to traditional country from their father, but also had certain rights in their mother’s country. From their mother, a person inherited their dilbayan or so-called moiety, i.e., one of the four possible sections or classes to which they could belong. This inheritance affected their choice of spouse. In addition, a person also inherited from their mother their yuri, the so-called skin or totemic relationship with certain animals. A person’s yuri placed responsibility on that person to care for the wellbeing of that animal, but also linked people, so for example, a person would consider all other people also belonging to that person’s yuri as their brothers and sisters.

In addition to divisions inherited through birth, a person was also given a role within their clan at the time of their initiation into adult life. For example, Jinibara men could be given the role of fisherman, hunter, tree climber, or maker of utensils and weapons; both men and women could become imarbara, those who, if requested, sang and pacified restless babies; and women became weavers, possum cloak makers, and specialists in gathering certain foods. These roles effectively became a person’s specialisation.

Almost all people, both girls and boys, went through initiation into adult life. However, if the individual chose to, they could attempt to pass through another six layers of initiation (seven levels of initiation in all). Becoming a songman or woman – a person responsible for preparing and performing songs about clan events, history and stories – required initiation through six levels; becoming a gundir – a person considered to have ngul or spiritual powers – was the highest form of initiation. Other than initiation into adult life, all initiation levels were voluntary and could be failed.

Contrary to popular perceptions, life for the Jinibara People in traditional times did not involve a relentless search for food. Rather, traditional country was bountiful, and individuals had their personal responsibilities for providing for the group. Nor did people move nomadically. Rather, each clan of the Jinibara People had a few places where camps were erected on an annual basis, providing people with a consistent lifestyle in an area for several months. Of course, smaller numbers of people used other camps as well, to move through their traditional country, or to take advantage of certain resources or ceremonial requirements. Camps were kept clean and hygienic, with traditional laws dictating where people established their houses, and where other activities occurred. When people became sick, medicines and special ceremonies were provided to assist their cure. Women during pregnancy and childbirth were cared for in ways that gave them considerable support. Older members of the group were also looked after.

People chose to visit other clans and tribal groups, often for festivals, ceremonies, and sporting functions such as wrestling games. Many people, including their Kabi Kabi neighbours, visited the bunya festivals held in Jinibara traditional country at Burun, now known as Baroon Pocket, and at Buruja, now known as Villeneuve at the base of Mt. Archer. In return, members of the Jinibara People used to visit gatherings in other traditional countries. People travelled through other traditional countries with the permission of those traditional custodians, usually following pathways which visitors were allowed to use. An example of such a pathway was approximately where Old Gympie Road now passes today.

Festivals and ceremonies provided a good opportunity for law-makers, muninburum (clan leaders) and elders to meet. For example, those men who belonged to the Bora Council, the group that managed bora (initiation) ceremonies, came together to make decisions on such matters. Headmen and women of a clan also met, to make decisions about inter-group matters, such as marriages and disputes. Festivals and ceremonies also provided a forum for trade between groups. Extensive trading systems existed across Southeast Queensland and northern New South Wales. The Jinibara People were famous for gugunde or black possum fur cloaks they produced, which they traded for diverse goods from other traditional countries.

In addition to the requirements of daily life, Jinibara traditional country is imbued with layers of meaning and symbolism that link each individual with the ancestral beings that created the country in ninangurra or creation time, njirani or ancestors who now live in the sky, yuri or totems and other ancestral animals and plants, and stories that hold powerful meanings. Unlike in many non-indigenous lifestyles, meaning and symbolism cannot be detached from daily life, as all these aspects of life are intertwined.

Today, the Jinibara People continue their connections with their traditional country, and maintain their places, areas and sites of significance. Specifically, a native title right held by the Jinibara People is to "maintain sites, objects, places and areas of significance to the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs and protect by lawful means those sites, objects, places and areas from physical harm or desecration".[2] Sites, places and areas are not always defined by tangible material evidence, but are only known to their traditional owners. Nor is the State’s register of area and objects comprehensive. Members of the wider community who have questions or concerns about areas and objects or wish to check that their activities will not impact on Jinibara places, areas and sites of significance are always welcome to contact the Jinibara People directly for advice.

[1] Traditional language provided in this document is specific to the Jinibara People’s dialects. Other traditional owner groups may have different words for the same item or concept.

[2] Agreement under S 87 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (No QUD 6128 of 1998)